Just 66% of millennials firmly believe the Earth is round,” says a YouGov study in the U.S. How is this possible among the most educated generation, with so much data and free access to AI? If you ask ChatGPT, “Is the Earth flat?” it straight up says “No” and thoroughly explains why.

You might blame this failure on a dumbing down of society as our minds wilt adrift in an infinite stream of clickbait and Instagram Reels. But the root cause of this flawed judgment about the world is a flawed thought process. We all use mental shortcuts like trusting or distrusting particular sources. Without these shortcuts, we’d go loopy from having to dissect every claim we encounter painstakingly.

The issue starts when trusted sources, like governments and top media, lose credibility. Their repeated lies push many to think, “If the mainstream says it, I’ll believe the opposite.” This is alarming. Despite their flaws, mainstream institutions are still more reliable than fringe internet groups. Learning to think critically sharpens our intuition about which sources to trust. It is our best defense against silly ideas like the flat Earth theory and far darker traps our minds can fall into.

Critical thinking also turbocharges your personal and professional growth. A 2019 survey asking HR Leaders about skills gaps ranked critical thinking as the leading “missing skill” in the U.S. workforce. Meanwhile, big data and AI are spinning up new opportunities and threats at a mind-boggling pace. The world is changing fast. Critical thinking is the best compass we have for navigating these uncertain waters. Yet our education system and corporate training plans lag. The critical thinking gap continues to grow. However, I believe we can and must close this gap! I’ll draw on my experience as a data analyst and corporate trainer to explore the following:

- What is critical thinking?

- Why critical thinking is the most vital skill in the age of data and AI.

- How to make learning critical thinking a joy.

What is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking means analyzing evidence to make better decisions. However, we can sometimes take shortcuts. For example, we might follow rules, imitate others, or stick to past successes. But we’re increasingly confronted with new problems that our shortcuts don’t work on. These novel problems force us to gather and analyze new evidence. Easier said than done, right? Let’s break it down into four steps, called the 4 As of critical thinking.

1. Ask Valuable Questions

Jotting down every wacky question that pops into your head is a great way to rip into a new problem. But we must pass each question through a filter and consider: If I already knew the answer, what would I do with it? How would the answer help me do something worthwhile? Once we’ve curated valuable questions, we can break big questions like “Why has our firm’s profit collapsed?” into smaller, more manageable questions like “Have our expenses increased?” and “Has our revenue fallen?”

2. Assemble Evidence

What evidence could help us answer our questions? Data is often our first port of call and can provide potent evidence. But let’s not overlook the basic step of talking to people close to the problem or the value of our intuitions. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos cautions, “When the anecdotes and the data disagree, the anecdotes are usually right.”

3. Analyze the evidence

Can we make a logical argument from our evidence for an answer to our questions? Sometimes logic hands us the answer on a platter. For example, our favorite pizza place is always closed on Mondays. Today is Monday. So, we know we can’t get our favorite pizza tonight. Our problems are rarely this simple. Typically, we can’t get 100% certain answers. We’re striving to understand how likely an answer is to be true. Depending on the problem’s importance and the evidence, we could estimate this likelihood. We could use methods from an educated guess to building predictive models.

4. Act on the analysis

We’ve done our analysis to understand which answers to our questions are likely to be correct. Good thing we already considered how we’d use these answers back in the “ask” step. Now it’s time for action! Frequently, we must convince other people that our arguments make sense if we’re going to get anything done. Therefore, we must be able to explain our reasoning clearly and persuasively.

The 4 As is a simplified model. We’ve only touched on a few key instruments in the critical thinker’s grand symphony. An omnipresent fifth “A” underpins the whole process—Attitude. Attitude is not a step. It’s a mindset of curiosity and a willingness to experiment, question conventional wisdom, and challenge our biases. Voltaire once observed, “It is dangerous to be right in matters on which the established authorities are wrong.” Adopting this mindset is a tough grind, as evolution has wired us to look for easy solutions, to fit in with the tribe, and not question the status quo. But transcending these instincts is the key to deep critical thinking.

Why critical thinking is the most vital skill in the age of data and AI

The arrival of big data and generative AI at our fingertips has created a tsunami of opportunities. If we want to ride this wave or stay afloat professionally, aren’t the most vital skills directly related to data and AI? In a sense, they are. Let’s start with data. Why do we want to analyze data? Data analytics and data science have the same end goal as critical thinking: making better judgments and decisions. To solve any new problem, we need core critical thinking skills. These include asking good questions, examining evidence, and building a logical argument. We can develop a better solution to some of these problems by analyzing data. Therefore, thinking critically is essential to doing anything worthwhile with data.

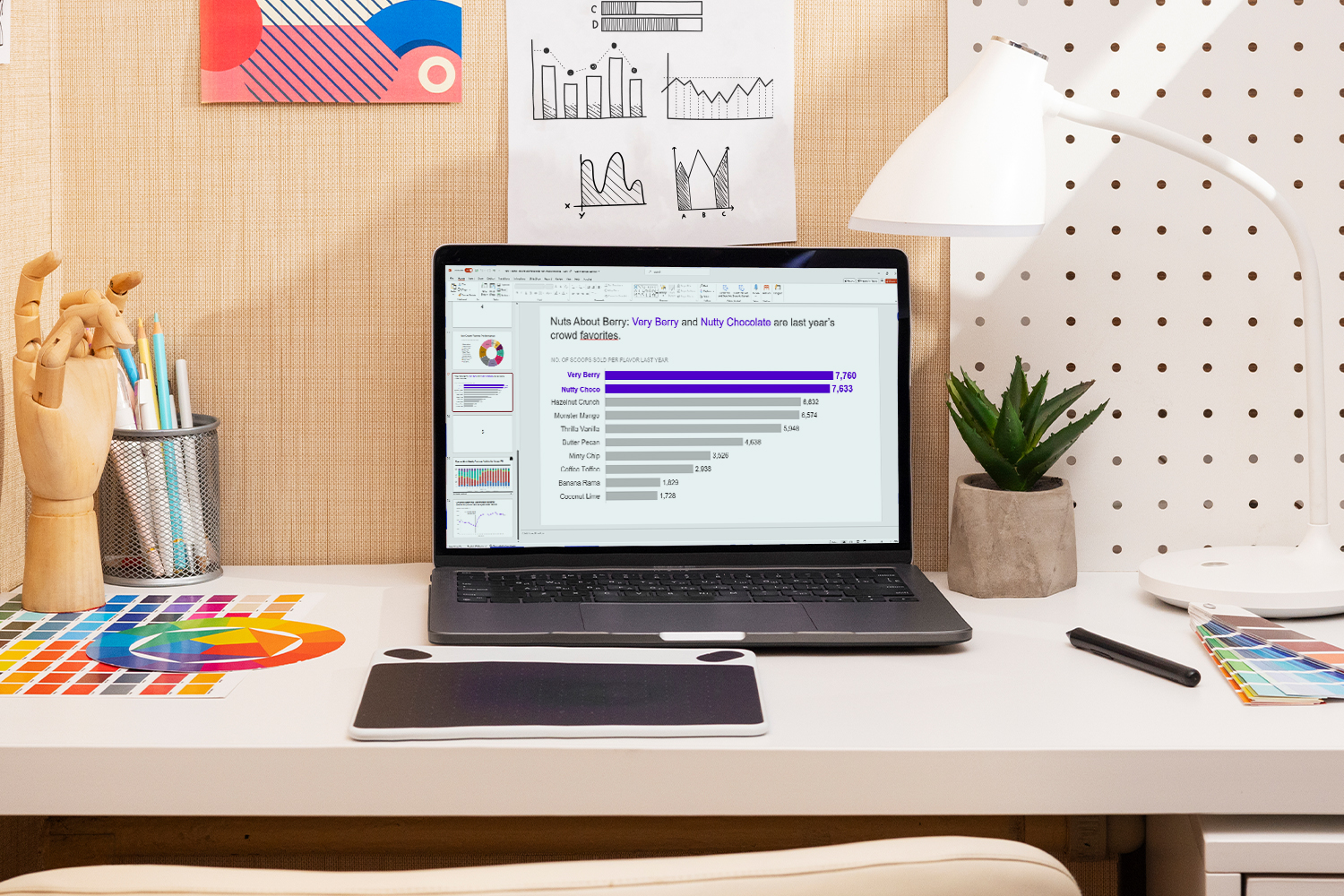

Sure, you can create complex data models without critical thinking. You can also rant about the Earth’s shape without knowing geography. But in my experience, models and analyses produced by people inept at critical thinking rarely do anything useful. A 2019 survey by VentureBeat AI reported that “87% of data science projects never make it into production.” The same year, a Gartner survey found that “80% of analytics insights will not deliver business outcomes through 2022.” We don’t know how many of these failures stem from a deficit of critical thinking. But it would have been wise to teach these people to ask valuable questions. They should have thought about how to use the answers before building their models.

I’m not trying to trash-talk data skills. I wholeheartedly agree they are valuable and growing ever more valuable. I must address the cult-like obsession with being “data-driven.” It assumes data is the answer to every problem. I can see how this mentality arises. Data analysis is an advanced tool that unlocks exciting possibilities. But cramming data into every problem is as bonkers as a doctor saying, “The MRI is the most advanced tool here, so let’s scan every patient with it.”

Brent Dykes defines a “data-driven” company as “oriented to make strategic and tactical decisions based on data rather than opinion or gut instinct.” Let’s look at an example of a company that went all in on placing data above intuition. Andrew Mason founded Groupon in 2006. By 2011, he’d taken it public with a $12.5 billion valuation, the biggest IPO since Google! At the heart of their business was a daily email offering their subscribers deals with heavy discounts on local experiences. Eventually, someone wondered, why not try running two emails a day? Andrew’s instinct was, “That sounds awful…who wants to get two emails every single day from a company.” However, Groupon prided itself on being a data-driven company. So, he agreed to run a test and let the data speak for itself. Unsubscribe rates did go up slightly, but purchases soared. The data had spoken. Or so it seemed.

In the long run, these unsubscribes compounded. Andrew believes it changed the very fabric of his company, admitting, “If you look at Groupon now, it’s just this kind of vestige of what it once was.” Today, Groupon has lost 98% of that $12.5 billion valuation. Looking back on the experience in 2018 after being fired as CEO, Mason reflected, “What I’ve taken away from that is there are some things where it’s like I’m sorry, I’m not going to look at the data on that…This is just what we’re going to do. And we know that it’s right, and there’s nothing that’s going to shake us from that.”

The lesson from this story isn’t to reject data and revert to the big shots deciding everything on gut feel. It’s that analyzing evidence is hard! It’s so much more than crunching numbers. It includes developing better intuition. We all make predictions based on intuition every day. We predict if we’ll enjoy a new restaurant or if a new house will increase in value. When was the last time you checked your past predictions against what actually happened to see if they were accurate? When was the last time you tested your intuitions for bias? When was the last time you wrote down a logical argument step by step to critique your reasoning? Even if you’re already a skilled critical thinker, the opportunities to improve are boundless. Andrew Mason was almost certainly a strong critical thinker back then. But what if he’d been even better? What if he understood the value of his intuition? It might have saved his company. Conversely, it’s hard to see how advanced data analytics would help. Data skills are valuable, but critical thinking is vital.

What about the impact of AI on our need for critical thinking? In 2022, a cruel new breed of AI-armed scammers emerged. The culprits just need to record their victim speaking for a few seconds. With the recording, they can use AI to synthesize an eerily accurate vocal doppelgänger. The scammers can then manipulate the stolen voice to say anything they want. They then, with no pity, demand money from victims’ families. They make up stories of illness, injury, and kidnapping.

This is the tip of the iceberg. Algorithms are already producing images of human faces almost indistinguishable from real-life photographs. Then, there’s the growing sophistication of deepfake videos. They can now be made with little to no technical expertise. The line between reality and artificiality may soon blur to the point of invisibility. Picture yourself on a video call, struggling to determine whether the person on the other side of the screen is flesh and blood or a virtual imposter. It’s a frightening scenario. And yet, the situation is not hopeless.

Consider Photoshop and its ability to create plausible fake photographs. We learned long ago to navigate a reality where photographs can no longer be taken at face value. Today, when we see an incredible image—like a photo of King Charles in a wingsuit, flying from the top of the Empire State Building—we don’t just accept it.

Instead, we apply the “4As” of critical thinking. So we ask, “Has this photograph been manipulated?” We could then assemble some evidence and analyze it using this argument:

- The Empire State Building is 1,250 feet tall.

- The minimum height for flying a wingsuit is around 2,000 feet.

- King Charles is still alive.

- Therefore, the photograph has been manipulated.

So, we act by ignoring the photograph. Finally, our attitude will change as we become more skeptical of all peculiar photos. Though we can adapt to these emerging threats, the task will grow harder over time as AI learns to fabricate more and more evidence that we could once rely on. Therefore, the need for more sophisticated critical thinking skills will only increase.

How to make learning critical thinking a joy

Human beings are intensely curious creatures. Our brains release dopamine when encountering fresh or surprising information. Dopamine is associated with feelings of pleasure and reward. We’ve all felt this delight of discovery. It could be a friend texting us a juicy story, or the joy of solving a crossword puzzle that has taunted us for hours. Critical thinking compels us to hunt for new evidence and piece it together to make discoveries. It should be a joyful experience. Here are six tips to ensure that it is.

1. Make it practical

Almost any training should get learners to apply and practice concepts. But it’s especially crucial for teaching broad, creative skills like critical thinking. There’s no shortage of fun games that help people understand key concepts. For example, the game 20 Questions teaches us about asking valuable questions and breaking down a problem. If you’ve never played, the game is simple. One player thinks of a famous person, and the other players get up to 20 yes or no questions to figure out who it is. The game continues until the players guess correctly or run out of questions.

Learners who play this game quickly realize they already have useful problem-solving intuitions. Most people will start with questions like “Is the person fictional?” or “Are they female?” These are good questions. They eliminate half the possibilities each time. That’s the most efficient way to search the entire problem space. Learners should be challenged to solve a meatier, overarching problem throughout the course. We find that a well-designed case study that’s realistic and a bit of a stretch to solve works wonderfully.

2. Prove its value

Critical thinking can easily get lumped together in learners’ minds with other “soft skills” of more questionable value. After a game like 20 Questions, we must tie what we’ve learned to practical, relatable use cases. We learned to ask good questions and break down a problem.

3. Teach with stories

There’s no shortage of real stories like that of Andrew Mason from Groupon. We can also immerse our learners in carefully written fictional stories as part of the case studies and challenges they solve. Stories should be our introduction point for each concept, rather than theory, frameworks, and jargon.

4. Cut the math and jargon (when introducing people to the topic)

A large proportion of college-educated Americans can’t remember high school math concepts. I’m not criticizing them. They have jobs where they haven’t needed their high school math for years or decades. In reality, throwing up formulas, even extremely useful ones like Bayes Theorem, is a surefire way to alienate many learners.

Similarly, there’s very little jargon required to learn some of the most valuable critical thinking skills. Notice how little I used in this article. A nasty example of unnecessary jargon is the double negatives describing “hypothesis testing.” I get the need to invent jargon for specialized concepts. The term “hypothesis testing” is within reason. But terminology like “we fail to reject the null hypothesis” is an abuse of language that should be banished.

5. Unbundle it from data training

In 2020, I created a training course called Data to Insights. It’s still a great course if you want to learn critical thinking and data literacy skills at the same time. It’s still based on the 4 As, but every step ties the process to data. This wedding to data could imply to learners that we need to use data to solve every problem, which could not be further from the truth.

Conclusion

Data and AI are only useful to the extent that discerning minds can put them to good use. Developing a discerning mind isn’t the latest sexy thing. It can be difficult, uncomfortable, even scary. But if you want to improve your life and the world around you, it’s the best investment you’ll ever make.

To learn more about data storytelling and other learning opportunities related to data communication, check out our scheduled workshops or contact us to set up a special class.

Learn with us and earn your certificate. See you at our next workshop!